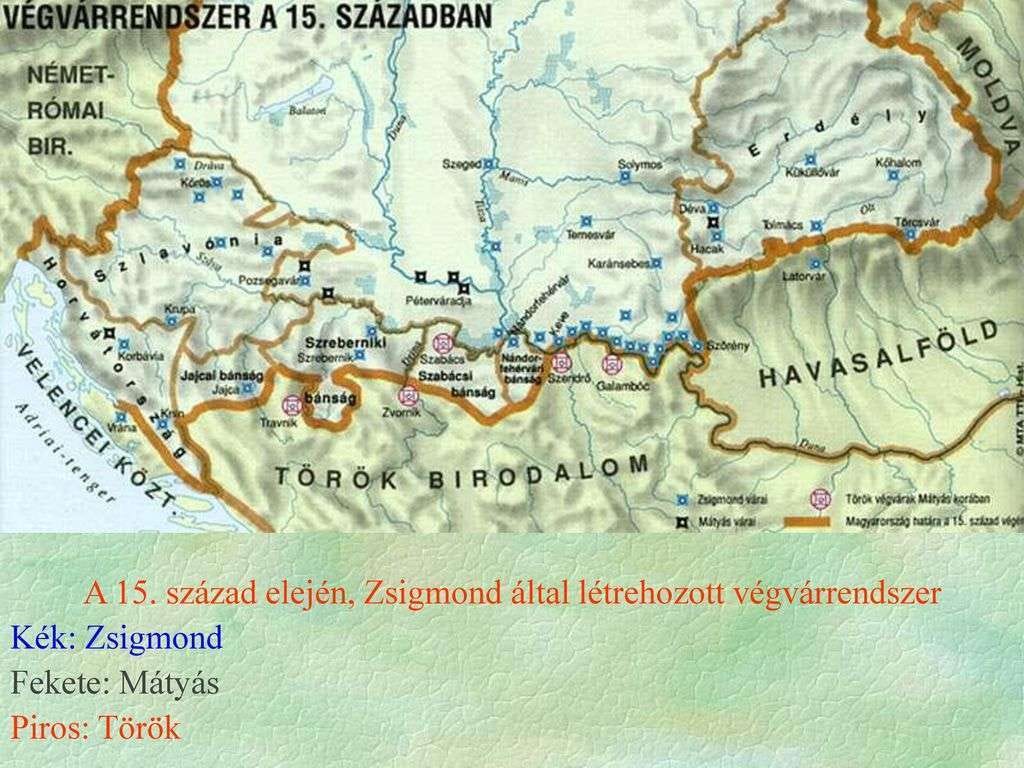

On 27 December 1426, the powerful Hungarian baron of Italian origin, who was known as an exceptional military commander, returned to the Creator. The construction of the fortress chain of the Hungarian border between Szörény and Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) on the Lower Danube is attributed to him.

Antonio Bonfini, the historian of King Matthias wrote about him: “He [i.e. King Sigismund of Luxemburg / Luxemburgi Zsigmond, reigned 1387-1437 ] forced the Turks to remain in peace in their own country, which he defeated in twenty battles through the Florentine cavalry captain Pipo.” (Antonio Bonfini: Decades of Hungarian History) Originally Filippo was also referred to as Pippo Spano (Comes Pippo) by the Italians but in Bulgarian and Serbian songs and ballads he is called “Magyar Fülöp” (Hungarian Philip).

Long ago, in the 14th century, there was a Florentine merchant called Scolari. He had a son. They lived quite well, but they were not among the rich nobility. In addition to his trade, Scolari had his son trained as a soldier, apparently so that he could protect himself and his goods on his longer journeys. Filippo – as the boy was called – is said to have arrived in Buda at the age of thirteen or fifteen with an Italian agent of a Hungarian lord, where he worked in Luca del Pecchia’s shop. But then he moved on to other things.

Why are we interested in this boy who lived 700 years ago? Did he at least leave something for our time? He wasn’t Hungarian! But he became one, and he had a career in Hungary that was second to none. Our oligarchs of today would be looking at his enrichment with a gaping mouth, and, for that matter, at the professionalism with which he managed his affairs.

Filippo Scolari has an authentic portrayal. Andrea del Castagno’s work, preserved in the San Appolonia Museum in Florence, depicts the young man in armor, sword in hand, with his wavy hair and his lean, wolfish figure. It was not only thanks to his good posture that Filippo caught the eye of one of Archbishop Széchy Demeter of Esztergom. He could read and write and was good at arithmetic, which is how he became first a scribe-deacon to the Archbishop and then a soldier serving in the family. The latter meant indentured military service and came with an oath of allegiance in return for an estate.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hungarian History 1366-1699 to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.